Bellingcat Investigator Peter Barth, who grew up in Texas, researched and reported this story in collaboration with the Texas Observer.

William “Bill” Asher Richardson Jr. pulled into the driveway of his upscale Corpus Christi home late on a Sunday night at the end of summer. The wealthy Texas oilman was unloading his Winnebago RV as his wife and stepson walked inside. Their housekeeper, watching through the front window, saw them first: two men, armed with sawed-off shotguns and wearing jumpsuits, running toward Richardson from the shadows.

Without a word, they fired four shells of No. 4 buckshot, sending 45 pellets into Richardson’s head, neck, chest, and arms. The shooters were gone as quickly as they arrived, fleeing in a getaway car. Richardson’s wife tried to call for help, but the phone line had been cut. Her son ran to fetch a neighbouring doctor. It was too late. Richardson, 40, died sprawled on his driveway.

Richardson’s murder on Aug. 1, 1971, remains unsolved.

Clicking on a note will take you to the relevant chapter of the story. You can return to this pinboard at any time by clicking Return to intro.

The case is one of an overwhelming number of unsolved homicides in the United States. The Murder Accountability Project (MAP) counts almost 346,000 cold cases of homicide between 1965 and 2023—likely an undercount since many homicides from the earlier decades are excluded and not all police departments report to the FBI Uniform Crime Reporting Program, on which MAP is based.

Clearance rates for US homicides—generally defined as the percentage of cases closed via arrest or the death of a suspect, or ruled to be justifiable—have been declining for years.

Meanwhile, online crowdsourcing efforts have sprung up to tackle cold cases including Uncovered, with almost 50,000 unsolved murder and missing persons cases, and Solve the Case, a nonprofit founded by Aaron Benzick, a detective with the Plano Police Department. “You highlight these cases, and people come forward,” Benzick told Bellingcat. “Even if that doesn’t happen, just organising these cases helps law enforcement.”

In 2023, the Corpus Christi Police Department (CCPD), with two detectives on its cold case squad, began reviewing 100 unsolved homicide cases dating back to April 1970—including Richardson’s. But the city has refused to release nearly all of its files.

Bellingcat has independently uncovered new information about the murder that’s never been made public. In a years-long open source review of Richardson’s murder conducted in collaboration with the Texas Observer, the outlets examined digitised newspapers, online archives, genealogy services, and declassified FBI records. The outlets also filed public record requests with local and state law enforcement agencies, the FBI, and the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA).

Two men, including one who did prison time for a prior murder, were charged with Richardson’s death but not convicted. The outlets’ investigation fleshes out the failed case against those two individuals and contributes new details to the public record of what happened the night Richardson was killed—including the possible identity of a getaway driver. The investigation also reveals alleged links between Richardson’s social circle and organised crime and some evidence of another potential participant in the crime.

The findings illuminate violent collisions between jet-setting Southern playboys at the highest rungs of the social ladder and the murky criminal underworld that gripped Texas in the 1960s and ’70s. Public records shed light on this peculiar clash of worlds, though enormous Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request backlogs, the loss of historical documents, and the unwillingness of law enforcement agencies to release all files make the full story elusive. Crucially, many players with firsthand knowledge—the witnesses, the alleged accomplices or killers, victims, police, lawyers, reporters, and family members—are either dead or unwilling to speak.

Richardson’s colourful life in a landed South Texas oil and ranching family was illuminated in older articles like “The Death of a Sportsman,” a 1971 feature published in the San Antonio Express and News. But, other than a single chapter in a 1997 book about a Texas Ranger, there are few recent media reports on the unsolved 1970s murder.

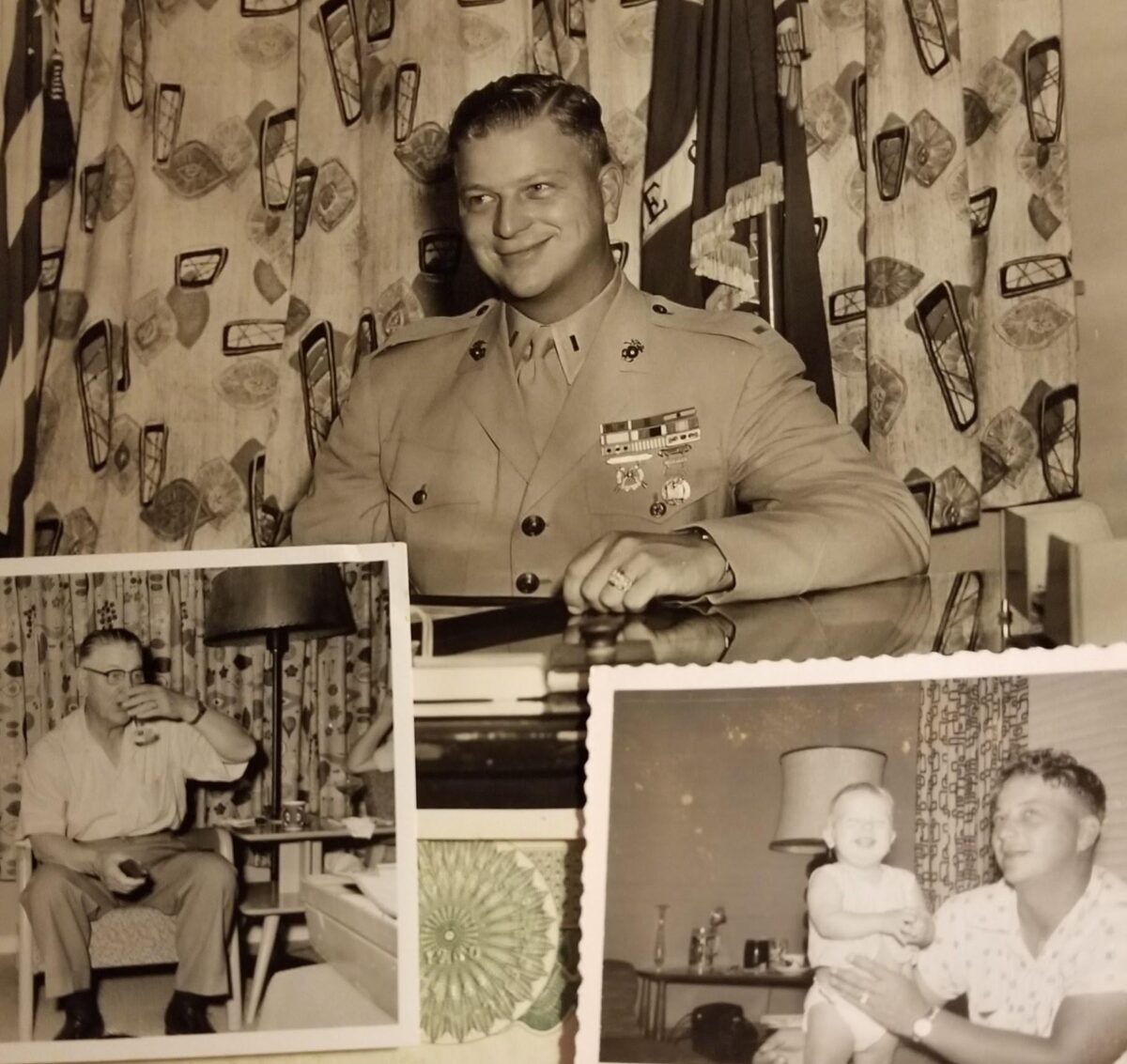

Family members have described the young Richardson as a troublemaker who attended three different high schools before dropping out. By age 20, he had joined the US Marine Corps and fought in the Korean War, where he was wounded and later decorated for his service.

His father, William Asher Richardson Sr., had founded the Richardson Petroleum Company. Richardson Jr. built his own company, Richardson Petroleum Enterprises, Inc. He spent weekends playing high-stakes poker, attending prestigious shooting tournaments, and on fishing trips in the Gulf of Mexico. He flew around in a customised P-51 Mustang fighter plane to manage his oil business.

Tragedy struck in 1963 when Richardson’s father, having fallen into financial strain, died by suicide. Lynn Richardson, Bill’s daughter and William’s granddaughter who was only six at that time, remembers hearing about her grandfather’s death. “A little boy came to the house with a grocery order for US$11, and he was so broke that he couldn’t pay that so he went upstairs and shot himself,” she told Bellingcat. Eight years later, her father was murdered in his Corpus Christi driveway. “It’s been really tragic. … They say there are generational curses. There’s just been a lot of violence in our family.”

In his final years of life, Bill Richardson’s oil business dried up, and in 1969 he filed for bankruptcy, owing about $3.3 million (around $28.7 million today). Roughly half of those debts were owed to 125 unsecured creditors, lenders that have no right to a borrower’s assets if they declare bankruptcy. Some were his enemies, business associates later told investigators.

Richardson turned to the sport of Columbaire-style pigeon shooting for income. A bloodsport popular in Spain, Mexico, and Argentina, it involves a skilled thrower—a columbaire—pitching live birds that are difficult for the shooter standing behind him to hit. Richardson was named one of the sport’s best shooters and was three times selected to represent America by its governing body.

Chapter 1: The Murder of a Texas Oilman

A previously unreleased offence report, obtained by Bellingcat in response to an information request, and an interview with a friend of the Richardsons conducted by Bellingcat add texture to newspaper narratives of the chaotic minutes before and after the murder.

Richardson lived with his family in a new four-bedroom house with a Mediterranean-style courtyard in Country Club Estates, an upscale neighbourhood in Corpus. On the night of Aug. 1, 1971, Richardson’s housekeeper, Mary Chavez, was helping the family settle in after a pigeon shoot in McAllen, Texas.

A stranger had called the Richardsons’ house to ask when the family would return, Chavez later told authorities, and she and others had seen suspicious-looking men around the neighbourhood. Police, who found a packet of cigarettes and empty beer cans in bushes near Richardson’s house, theorised that the gunmen had been lying in wait.

Around 11 p.m., Richardson and his 11-year-old stepson James LaBarba were unpacking their motor home when Chavez, from a front window of the house, saw two men running across the lawn with shotguns. Both were wearing baseball caps and sunglasses. She later described one as tall and lanky, the other as shorter and heavyset.

After the first shot, James turned and saw the men firing sawed-off shotguns at his stepfather. The coroner later logged 45 entry wounds. Investigators described the murder as a “professional killing.”

Bellingcat interviewed one of the first people to arrive at the crime scene, Chip Hogan, the son of Bill’s close friend and fellow pigeon shooter Roger Hogan, who was a teenager at the time. He and his father had accompanied Bill and his family on the trip to McAllen and had just arrived at their home after leaving Richardson’s house when the phone rang.

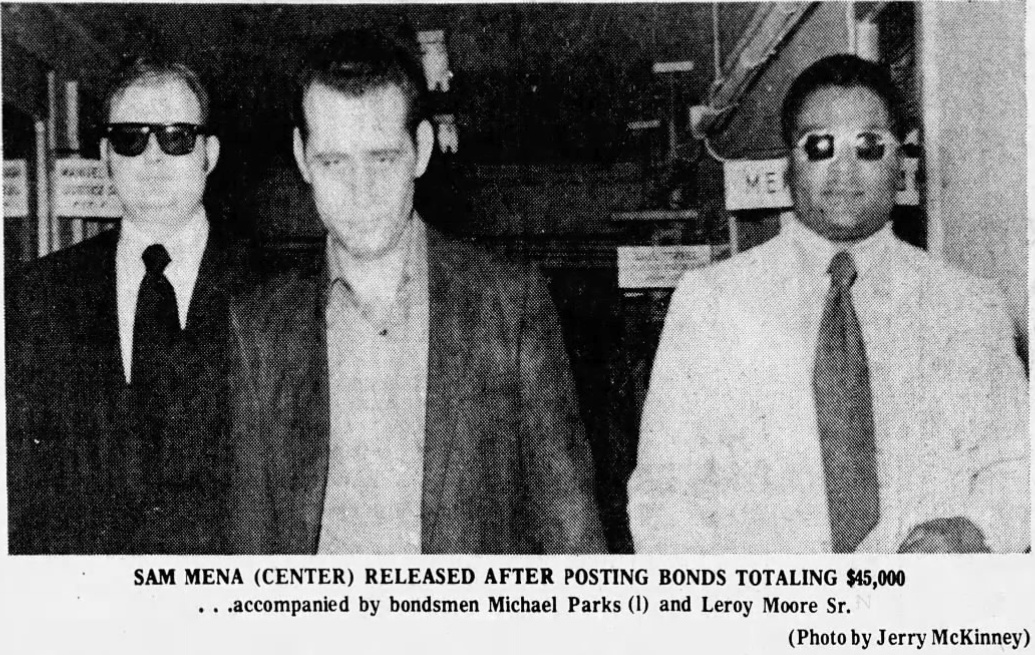

When shown possible suspects’ photographs, Chavez allegedly pointed to two men from Fort Worth: Odis Thomas Hammond and Sam Mena. Both of them were arrested for the killing.

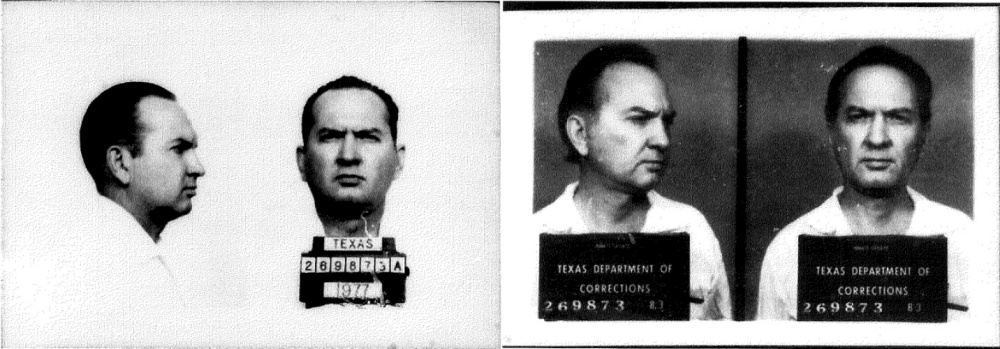

Hammond was a career criminal with an arrest record for burglary and a reputation with police for promoting prostitution. Richardson was the third person Hammond had been accused of killing, according to a Bellingcat review of Texas Department of Public Safety electronic records and detailed reports obtained through public information requests.

A June 10, 1957, WBAP-TV newsreel showing Hammond (right) giving the Fort Worth Assistant District Attorney a statement on killing his friend in self-defence the day before. Source: NBC 5/KXAS Television News Collection (AR0776), University of North Texas Special Collections.

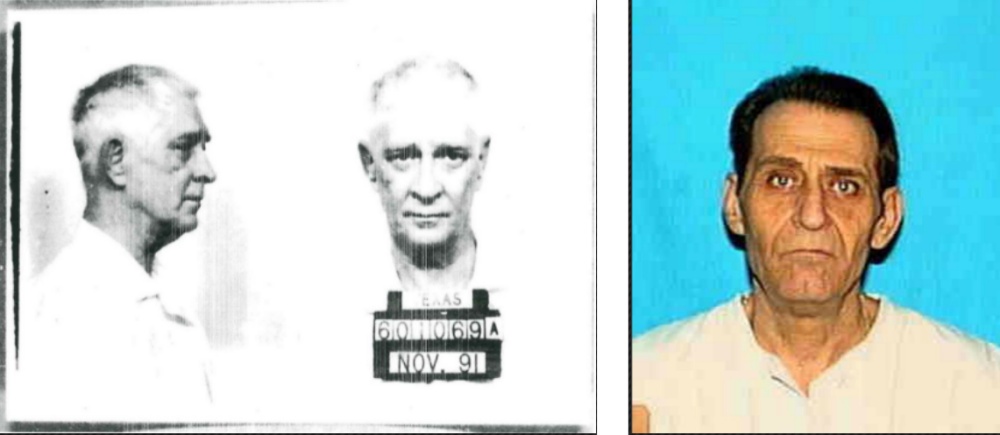

Hammond confessed to killing a friend and fellow pimp in a shootout outside a bar in Fort Worth in 1957, but he was never prosecuted after a witness failed to appear. Two years later, he was convicted of the 1959 murder of a Houston car salesman during an armed robbery. But, surprisingly, Hammond had done little prison time: He was sentenced to 30 years in 1962 but was paroled in April 1971.

Hammond had reportedly been arrested more than 60 times in Fort Worth when he was nearly killed by a woman who shot him in the stomach at a bar in 1958. He and two others also had been accused of opening fire on a man during a failed 1959 Midland robbery. In response to a FOIA request from Bellingcat, NARA released a 20-page FBI file on Hammond from a White-Slave Traffic Act (Mann Act) investigation in 1959, detailing FBI agents’ unsuccessful efforts to locate a woman they believed Hammond had trafficked out of state.

Sam Mena also had a significant criminal history, including arrests for burglary and robbery, and a 1959 jail escape, newspaper articles and records show. While jailed for Richardson’s murder, Mena allegedly tried to use a cellmate to recruit a contract killer to kill Richardson’s housekeeper before she could testify as a witness against him and Hammond. According to Corpus Christi police officers’ testimony, the contract killer was “Tommy” Gibbs.

But a cellmate tipped off police to the plot. Detectives were watching Chavez’s house when Gibbs drove to Corpus Christi shortly after Mena’s arrest. Police followed, and Gibbs apparently abandoned the plan. Six weeks later, Gibbs was shot to death in Fort Worth. His murder remains unsolved.

Despite all of the allegations about Hammond and Mena neither man was ultimately convicted of the notorious Corpus Christi killing.

Chapter 2: The Suspects—and Their Getaway Driver

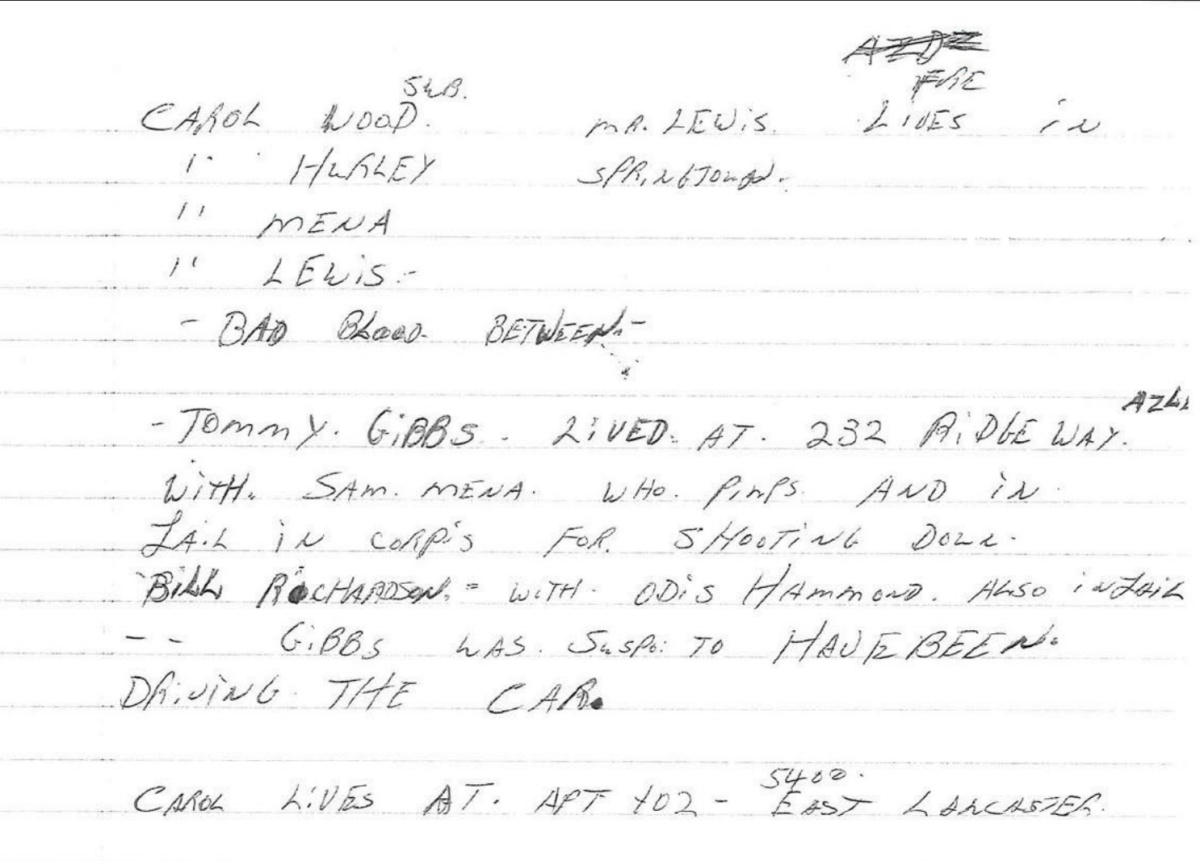

“Tommy” Gibbs, the would-be hitman, had another never-before-published connection to Richardson’s murder: Police suspected he had been the getaway driver, according to Gibbs’ homicide file, which Bellingcat obtained from the Parker County Sheriff’s Office.

Gibbs was a professional underworld operator who used multiple names, according to an analysis of newspaper reports, birth and death certificates, census data, prison records, and a prisoner-run newspaper. His real name was Paul Adams Gibbs, and he used the aliases George Edward Thomas and Tommy Gibbs. A former Marine wounded at Tarawa, Gibbs was arrested in 1944 for stealing a car and, by 1950, was serving a prison term for theft.

In 1951, he and two associates were arrested for beating and robbing a man, then throwing him out of a car. Gibbs was later detained in Dallas as part of a nationwide sweep of drug traffickers and did time for armed robbery. He’s described as an “alleged hitman” in the 1997 book by author Lee Paul about Jim Peters, a Texas Ranger who worked on the Richardson case.

Gibbs himself died mysteriously only months after failing to carry out a hit on Richardson’s housekeeper, one of the witnesses to the murder. On Nov. 14, 1971, a deer hunter in a wooded area near the town of Weatherford stumbled across a man in a suit and tie lying in a pool of blood. Police believed Gibbs had been executed and that his body had been dragged there from the trunk of a car. He’d been shot six times in the face, with a cheek wound delivered at such close range it caused gunpowder burns.

The Parker County sheriff’s newly released files on his homicide include a handwritten investigator’s note that says: “Tommy Gibbs. Lived at 232 Ridgeway, Azle (Texas) with Sam Mena who pimps and in jail in Corpis [sic] for shooting down Bill Richardson with Odis Hammond. Also in jail. Gibbs was susp. to have been driving the car.”

Some journalists speculated that Gibbs’ death was tied to a feud between members of the so-called Dixie Mafia, a loosely knit group of underworld crime figures that operated in Texas and other Southern states. Curiously, only two weeks before his murder, Gibbs had been shot in the leg but told authorities the injury was self-inflicted.

Jesse Sublett, author of two books about the Texas underworld of the 1960s and 70s said the Dixie Mafia was not structured like other crime gangs: “From the outside, ‘Dixie Mafia’ was a conceit, a marketing term so that law enforcement and the media could conceptualize the problem and sort of identify their approach to dealing with what was basically a criminal subculture of loosely associated people who tended to live outside the law.”

Police officials never revealed that they suspected Gibbs had been an accomplice in Richardson’s murder. By the time of the trial, he was already dead.

Chapter 3: The Failed Murder Trial

Odis Hammond was tried for Richardson’s murder on Aug. 21, 1972. Hammond’s lawyer moved successfully to have his client tried separately from Mena because, he argued, the evidence against Mena—which included statements he’d arranged for Gibbs to kill Richardson’s housekeeper—could harm Hammond’s case.

The prosecution called witnesses who placed Hammond near Richardson’s hotel in McAllen during the shooting competition and later at Richardson’s home on the night of the murder. A hotel clerk recalled that Hammond told her he’d made the 500-mile drive to McAllen from Fort Worth in a car customised to run on both butane and gasoline. Chavez and LaBarba, Richardson’s stepson, both identified him as one of the killers.

But then the case against them fell apart.

Hammond’s defence attorney questioned how witnesses could have seen the men clearly in the dark. He also called an FBI firearms expert, who testified that spent shells from the scene could not have come from the type of shotgun LaBarba claimed to have seen the killers fire.

The court blocked prosecutors’ attempts to show similarities between Richardson’s killing and a 1959 murder for which Hammond had been convicted. In that case, Hammond and an accomplice gunned down a Houston car salesman in his apartment. Hammond was paroled months before Richardson’s murder.

Other witnesses testified that Hammond had been in Fort Worth the weekend of the murder. One woman claimed she’d spent the night with him there. Hammond was found not guilty and walked out of court before the handcuffs he’d been wearing for trial had been unlocked, wearing sunglasses, and a smile on his face. (By 1977, he was arrested again for robbing a pharmacy in Dallas: He appeared to be wearing a wig when he pulled out a pistol, swiped narcotics, and escaped on foot with an accomplice from the 1959 Houston murder, records show.)

Nueces County prosecutors, having failed to convict Hammond, never prosecuted Mena for Richardson’s murder. But, as a felon, Mena also had been convicted of illegal possession of a handgun and did time in prison. By 1974, he was accused of accepting a contract to kill Tarrant County District Attorney Tim Curry, a plot that failed.

Ten years later, Mena, then 49, was arrested in Houston, this time for dealing cocaine to an undercover policeman. The police report, obtained by Bellingcat, describes Mena sporting a moustache, an all-denim “Canadian tuxedo”, and carrying a loaded .38 revolver.

Both Mena and Hammond spent the rest of their lives in and out of prison before dying in the 1990s. Neither ever confessed to Richardson’s murder.

Chip Hogan, the son of Richardson’s friend, told Bellingcat that he was asked to identify a man in a police lineup who was seen in the crowd at the pigeon shooting tournament in the days before Richardson’s murder. He also recounted a car briefly following Richardson, Jerry LaBarba and his father as they drove home in their separate cars on the day of the murder.

When shown photos of Hammond, Mena, and Gibbs, Chip Hogan told Bellingcat, “Hammond is familiar, the vision I have of him, his hair was combed, and I was thinking his hair colour was a lot lighter actually, more on the blonde side. He could have had his hair dyed or I’m completely wrong on his hair at that time”.

While the Corpus Christi police identified those two men as hired killers, prosecutors admitted to being at a loss for who had contracted them or the motive. Later, more leads arose from the seemingly unrelated murder investigation of yet another wealthy Texan.

Chapter 4: Another Corpus Millionaire Killed—and Chained to a Block of Concrete

On June 6, 1972, almost a year after Richardson’s murder, a corpse washed ashore on Mustang Island, across the causeway from the mainland portion of Corpus Christi. A fisherman was shocked to find the corpse chained by the neck to a concrete block.

The police quickly identified the dead man as 32-year-old George Randolph “Randy” Farenthold, a local millionaire whom Texas Monthly called “a playboy euphemistically described as a ‘sportsman’”. Farenthold had befriended Richardson through the high-stakes gambling and pigeon-shooting scenes. (He was the stepson of Francis “Sissy” Farenthold, a prominent state legislator.)

Randy Farenthold was also a key government witness: He’d been scheduled to testify in a federal fraud trial against four men accused of swindling $100,000 from him in an elaborate scheme involving the purchase of Treasury notes the men claimed were owned by the Mafia. His murder came weeks before the trial was due to start. Without the key witness, the case collapsed.

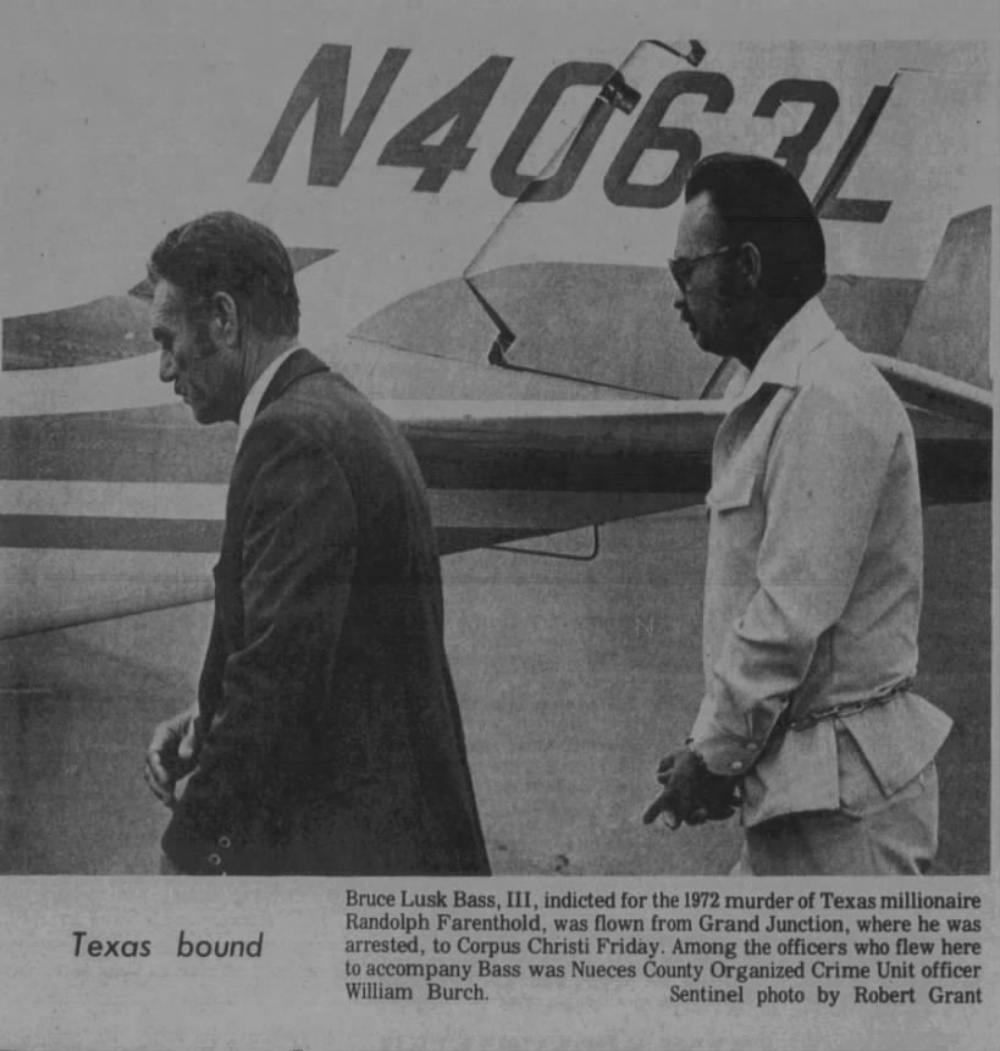

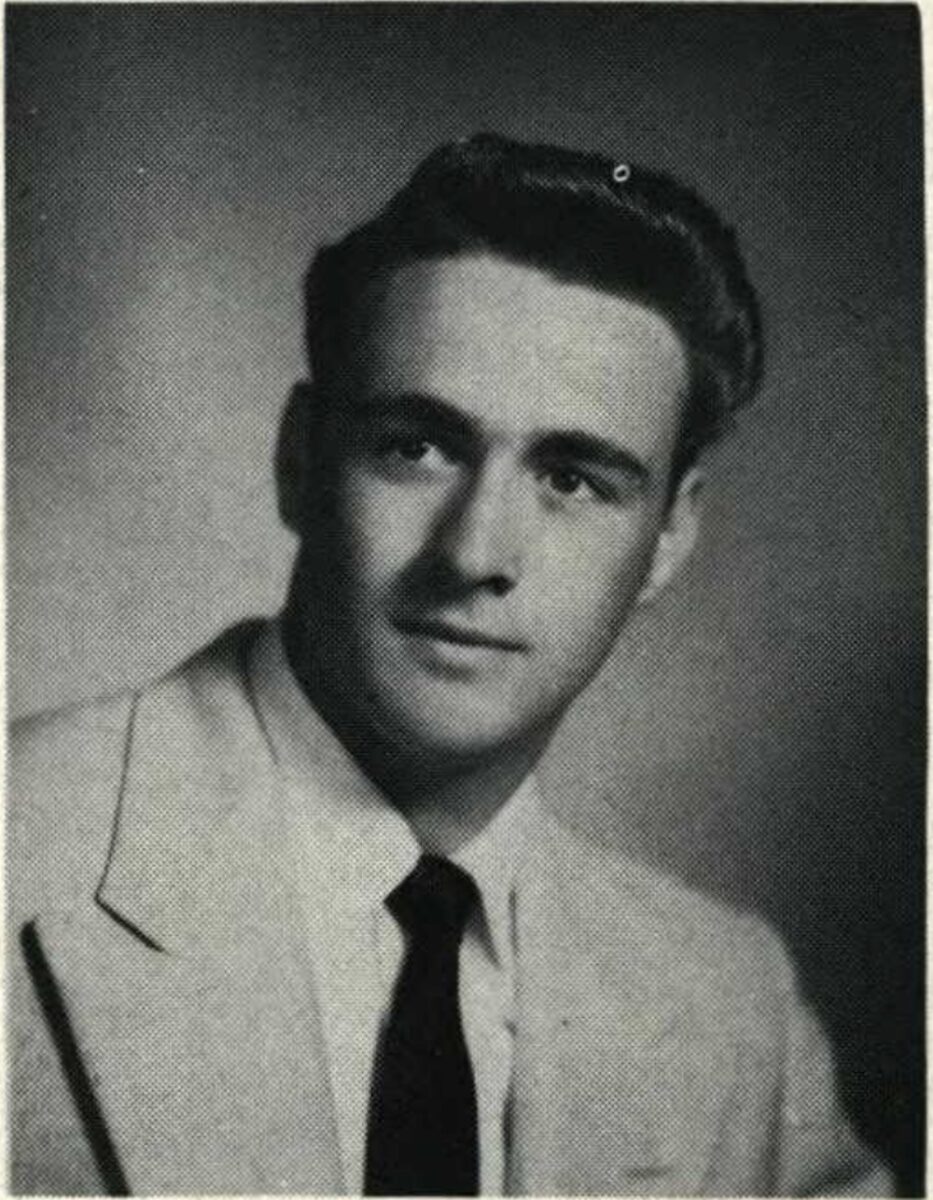

Two of the men accused of defrauding Farenthold, Bruce Lusk Bass III and Tharel Smith, were partners in a Corpus Christi construction firm. Bass was part of the same pigeon-shooting and gambling clique as Richardson and Farenthold. (“Richardson was involved with bookmaking,” a Corpus Christi police captain told reporters. “Farenthold was hanging around with the same people.”)

A break in the Farenthold murder case came when Robert “Little Bob” Walters, a man in prison for helping with a jailbreak, agreed to testify against Bass. Walters told a grand jury that he helped Bass and Smith dispose of Farenthold’s body after the two had kidnapped and fatally beaten and strangled him.

Walters also testified that Bass had confessed to being a participant in Richardson’s murder. It’s unclear if Walters knew more, since the rest of his grand jury statement remains under seal. In many other cases, so-called “jailhouse snitch” testimony has also often proven unreliable.

Portions of Walters’ grand jury statement are found in the book about Ranger Jim Peters and in newspaper articles. According to Walters, Bass was furious with Richardson because he thought he was being pushed out of a high-stakes gambling operation the two participated in. After pigeon shoots and on private jet flights to the Bahamas, this exclusive circle allegedly placed bets of up to $50,000 ($388,000 today) on games of dice.

According to Walters’ statement, Bass called him on Aug. 1, 1971, and said he planned to kill Richardson later that day. After Richardson’s murder, Walters said Bass asked him to dispose of a shotgun and he threw parts of it into a storm drain and into Oso Creek near Corpus Christi. Despite a search of Oso Creek, authorities never found any evidence to support his allegations.

Bass pleaded no contest to Farenthold’s murder and was sentenced to 16 years on June 20, 1977. Smith, his business partner, also implicated by Walters, was never charged and died of a heart attack in 1985. Neither was ever charged in the Richardson murder.

Lynn Richardson, Bill’s daughter, told Bellingcat her father knew Bass well. “He was a pigeon shooter. They were all in the pigeon shoots together,” she said. “Bruce Bass was actually a pretty good shooter.” A 1964 photo published in the Corpus Christi newspaper showed Bass and Richardson shaking hands after a tournament.

She recalled an incident at a hotel following a pigeon shoot in McAllen in the early ’60s when, as a young child, she jokingly pushed an apparently drunk Bass into the pool. Her father quickly jumped in, pulled up Bass, and scolded his daughter.

Bass was released from prison in 1983 after serving only six years for murdering Farenthold; a year later he was seriously wounded in a shooting in a Jackson, Mississippi, motel bar.

Two months later, on the 12th anniversary of Farenthold’s body washing ashore, Bass argued with the owner of a Corpus Christi club and was gunned down in the parking lot. The shooting death was ruled a case of self-defence.

Chapter 5: Alleged Organised Crime Connections

Bass and others in Richardson’s inner circle had alleged ties to organised crime, according to newly uncovered documents—including FBI records posted online and documents provided to Bellingcat via FOIA requests.

In July 1966, five years before the Richardson murder, FBI investigators raided the offices of Kress Manufacturing Company in Tulsa, Oklahoma. The owner, Jack Edward Kress, was wanted on gambling and conspiracy charges issued in Biloxi, Mississippi, a centre of Dixie Mafia activity. Kress Manufacturing had been producing and distributing illegal gambling equipment, including loaded dice and altered playing cards, which were being shipped nationwide. FBI investigators on the case looked at two Texans: Bruce Bass and James “Jerry” LaBarba.

Bass and LaBarba were Richardson’s friends and shooting companions. LaBarba was also the ex-husband of Richardson’s wife—and the father of Richardson’s stepson, the young man who had witnessed his murder.

FBI documents released for LaBarba and Bass include a mysterious account of a violent incident, involving illegal gambling, years before Richardson’s murder. On Dec. 23, 1967, two Portland, Texas, policemen spotted a car stopped along Highway 181 at about 2:30 a.m. Five men were in and around the car, including two in the front seats near loaded pistols. A man in the backseat was bleeding from a head wound that he attributed to “a slight misunderstanding and scuffle.”

All five were arrested, and a search of the car turned up nearly 800 sets of dice, some described as “crooked,” along with handwritten lists of Louisiana nightclubs. While the FBI redacted the names, the report’s inclusion in LaBarba’s FBI file suggests he may have been one of them, and the presence of an inventory of the confiscated dice in Bass’ FBI file suggests he was another.

Defence attorneys for Hammond claimed during the Richardson murder trial that LaBarba had told them he knew who had really committed Richardson’s murder. LaBarba separately testified that he had tried to protect his son by telling “lots of people” that James saw nothing on the night Richardson was killed. In an apparent reference to Randy Farenthold’s murder only two months earlier, LaBarba told the court this was because “It seems like witnesses have a real hard time staying alive in Corpus Christi”. (LaBarba died in 2009 and his son James died in 2018.)

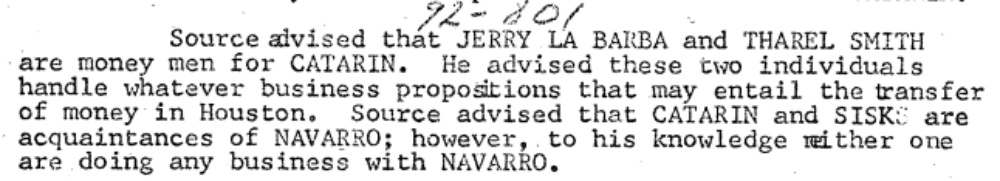

An unnamed informant told an FBI agent in 1972 that Jerry LaBarba and Tharel Smith, Bruce Bass’ business partner and alleged accomplice in Farenthold’s murder, had been working as “money men” for a prominent Dallas nightclub owner, Anthony “Tony” Francis Caterine. Caterine was an associate of Jack Ruby, another Dallas nightclub owner who gunned down JFK assassin Lee Harvey Oswald in 1963. Caterine was investigated by the FBI for racketeering and links to infamous New Orleans Cosa Nostra boss Carlos Marcello. (The FBI informant was identified only as HO 1994-PC. Their relationship with the FBI was ultimately terminated for “being unproductive.”)

However, his allegations line up with other FBI documents released under Bellingcat’s FOIAs, which connect Bass and Jerry LaBarba to gambling and suggest that Richardson’s friends and associates were involved in gambling and racketeering both before and after his death.

A final tantalising line of inquiry into the criminal intrigue surrounding Richardson, Bass, LaBarba, and their pigeon-shooting and dice-rolling associates concerns a “Georgia banker” briefly mentioned in newspaper reports and the book about Jim Peters, the Texas Ranger. (Peters is dead, and any reports he may have written on the Richardson case have not been released.)

The banker, Lamar Hill, frequently chartered planes in the 1970s to Texas, Las Vegas, and the Caribbean, reportedly to gamble with friends. In 1973, Hill was convicted in a massive embezzlement case, after stealing more than $4.6 million (about $34 million today) from his bank over 21 years. When asked by reporters how he’d spent it, Hill replied: “I just don’t know. … That’s a hell of a lot of money.”

In Paul’s book, the author asserts that Peters claimed Richardson and Bass belonged to the same secretive gambling circle as a man who fits Hill’s description: “an influential banker in Georgia … prosecuted for embezzlement.” Paul wrote that the banker “testified that it was his practice to fly a bunch of gambling members to the Bahamas, and they would gamble on his plane, spend a couple of days in the sun, and fly back.”

Loose Ends: Police Files Likely Contain More Clues

It is likely that law enforcement agencies’ files hold more clues that could help solve Richardson’s murder. The FBI, for instance, has more than 12,000 pages and more than two hours of audio recordings related to Bellingcat’s request for records on Bruce Bass. But it released only 29 pages.

The waiting period to receive all of these files, a spokesman said, is six-and-a-half years. And the FBI has more files on Tharel Smith and Jerry LaBarba, too.

The CCPD, which told Bellingcat it was reviewing the Richardson case “to determine whether it can/should be considered ‘closed’,” likely holds the most relevant cache of documents. Bellingcat and the Texas Observer have argued to the Nueces County district attorney that those documents should be released in the public interest—but the outlets are still waiting for a response.

Anyone with information regarding the unsolved homicide of William “Bill” Asher Richardson, Jr. is strongly encouraged to contact the Corpus Christi Police Department’s Robbery/Homicide Unit at 361-996-2840. Callers wishing to remain anonymous can submit tips through Crime Stoppers at 361-888-TIPS (361-888-8477) or online using the Crime Stoppers App.

Peter Barth is an investigator at Bellingcat whose work focuses on organised crime. Contact him at peter@bellingcat.com.

Gyula Csák, Lise Olsen, Beau Donelly, and Tristan Lee contributed research for this article. Interactive graphic by Logan Williams. Illustrations by Ann Kiernan, audio clips by Charlotte Maher and Merel Zoet.

Bellingcat is a non-profit and the ability to carry out our work is dependent on the kind support of individual donors. If you would like to support our work, you can do so here. You can also subscribe to our Patreon channel here. Subscribe to our Newsletter and follow us on Bluesky here and Mastodon here.

The post Pigeon Shoots and Hitmen: New Leads in a Texas Oilman’s Cold Case appeared first on bellingcat.